Shocker: the author of ‘The Illustrated Woman’ is writing about tattoos this week. In other news, bears have been known to defecate in woodland areas. Or so I’ve heard.

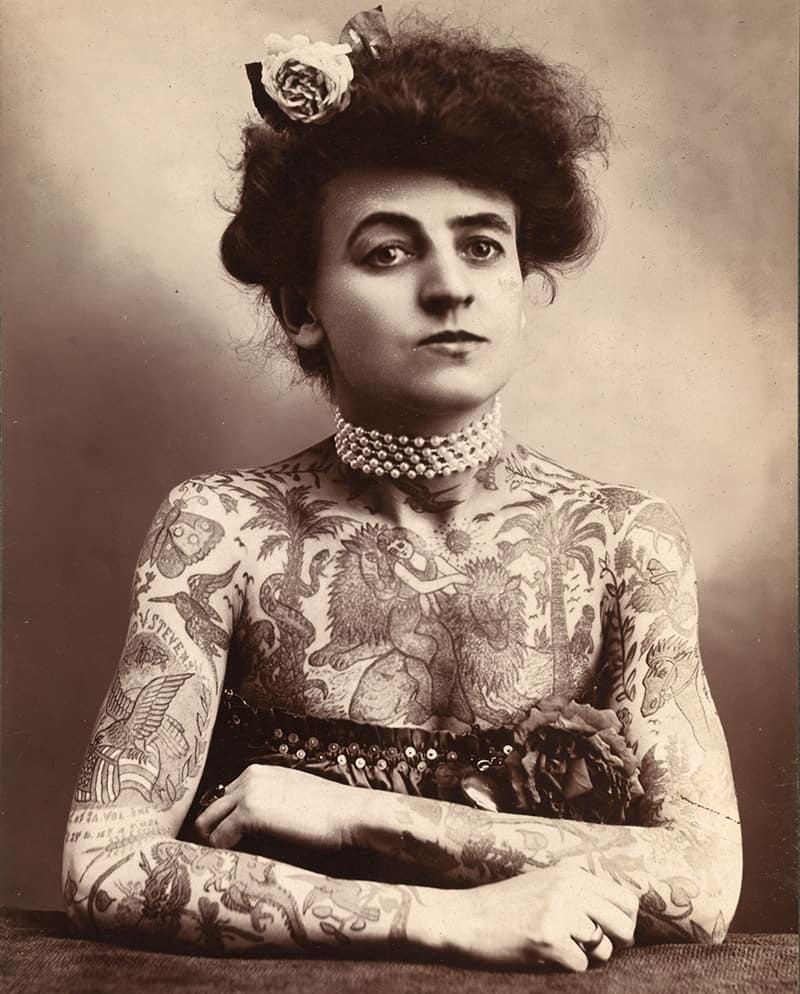

Above: image of Maud Stevens

Tattoos are strange signifiers of time and place. I can look at mine and recall fixed points of time, fixed states of mind that led to their inception. They occupy space. They turn the body into a kind of map, give it the illusion of readability. They are time-bound (living as long as the person they’re inscribed upon) but in some cases they seem (like poetry) a stab at immortality, an attempt to become art.

The following is an unpublished mini-essay that connects tattooing to my mum’s garden. I know, I know. She’s shaking her head in disapproval, surely.

*

Assorted blooms

‘The body, like the unconscious, surpasses the knowledge we have of it’ - Gilles Deleuze.

My mother cultivates a hundred different kinds of clematis. Her garden, on the outskirts of a former mining village, is a violent surge of colour. Traveller’s Joy. Virgin’s Bower. Old Man’s Beard. Leather Flower. So many names, so much also known as… I cultivate wounds, thoughtful, decorative scars on the surface of my body. The ink climbs up my calves and twines around my arms, torso and neck like a vase vine. I am a crowded garden. We are running out of space.

My mother’s garden was on a TV show once, though she asked them not to show her face and they never revealed the location. Instead, the screen filled with bold purples and crepe-paper pinks, close ups of the petals. A man in a crisp shirt and beige chinos was standing on my mother’s lawn, singling out the most interesting specimens. Markham’s Pink. Polar Bear (or Arctic Queen). Miss Bateman. Prince Charles. Princess Diana. The eye of the camera followed the leaves as they divided into leaflets and leafstalks, twisting and curling around fenceposts and through other plants. Clematis are master climbers. They know how to entwine and to be entwined. As I watched, I wished the red-faced presenters had said where they were filming. All these hardy, pushy flowers, thriving where open casting had stripped the ground. Tendrils getting their point across, finding a way through.

When I was a kid, I wasn’t allowed to have my ears pierced. By the last year of primary school, all my friends wore neat, gold studs or little hoops that caught the light. I was fascinated by the idea of the piercing gun, imagining it really fired tiny bullets. I loved the thought of earlobes and cartilage admitting those fragments, such brightness. But I couldn’t go inside the jewellery shop. It became one of many mysteries, like the houses at Arkwright just down the hill from us that moved across the road in stages, a new estate replacing the field where three stately trees had stood for centuries, the old village and the old pit shafts cleared and excavated

Open cast mining was the greatest puzzle of all to me as a child. I didn’t understand what they were looking for. What was in the rubble? I had a vague understanding of mining and its decline, achieved from the privilege of a certain distance: none of my family lost their jobs due to pit closure, after all. Further away from our house, there were green, artificial hills, too perfect, and my mother explained that they were landfill. As if the ground had sprouted bumps and ganglions made from all our wasted things.

My mother is resourceful as a clematis. She would spend weekends collecting rubbish from the roadsides, taking it all home in the boot of the car to dispose of (still does). I was a reflection in the back passenger-side window, imagining everything kept hidden under the ground, all the diggers desired and all that we’d rejected.

A tattoo lives both under the skin and on it, depending on what you understand the skin to be. We are made of layers, onion-like. The epidermis is always changing. A tattoo inked here would vanish (and my recurring anxiety dream is that mine do, the ink whitening and then gone entirely, or the woman above my left kneecap walking clean away from my body). The dermis is the layer below, anchored by subcutaneous fat to the muscles and bones. It is in charge of growing hair, making sweat, conveying blood. If bodies were subject to open casting, it would be at the level of the dermis. This is where a tattoo lives. If the needle went too deep and punctured the layer below, the ink would spread and ‘blow out’, blooming then disappearing, eliminated through the body’s natural healing processes, an unknown presence. When I get tattooed, my blood blooms from the wound and colour blooms from the needle. Heavy metals, altering my composition, mingling with my cells. A work of art which changes with its canvas and - ultimately - dies with the frame.

The clematis varieties in my mother’s garden look both indestructible and natural, but they are neither. They are threatened by snails, aphids, earwigs, slugs, by powdery mildew and ‘green flower disease’. And they harbour their own quiet danger. If you were to ingest the compounds found in clematis in large amounts, you’d suffer internal bleeding of the digestive tract. First Nations Americans used small quantities to treat migraines and nervous disorders (both of which afflict my mother), but their dosage was careful. Nor do they ‘belong’ to the soil that she has chosen for them. Native to Japan, they were introduced to Europe in 1836 by a Dutch doctor, Philipp Franz Balthasar Von Siebold, who also brought Japanese knotweed. While living in Japan, Von Siebald fathered a child, Kusomoto Ine, a woman who would go on to become the first Japanese doctor schooled in Western Medicine. For all his apparent social ‘integration’, his departure was scandalous. He was accused of being a spy after he got hold of various forbidden maps detailing Northern Japan and exiled. He took the clematis with him, cultivated to endure the Dutch climate. He extracted those flowers, grafted them. As easy and difficult as relocating a village, I assume.

I think I could grow to understand the thrill that must come with the process of building and maintaining a garden, the illusion of control. It is the same process I engage in with my own body, curating it through modifications, watching as my kneecaps and forearms and shins and collarbones and ribs and sternum and feet become dense with ink. Alessandra Lemma, psychotherapist and author of Under The Skin, argues that ‘as a species, we clearly have difficulty managing our embodied nature.’ Perhaps our difficulty is not with the body per se, but its evolution and existence in the presence of fellow humans. We both seek and fear scrutiny.

According to Sartre, ‘the look’ is the domain of domination and mastery. We exist through the other, we come to know ourselves through their stare. In this, we experience dependency. And, Lemma argues, we learn this first through our mothers, through shared corporeality and then the insistence - or absence - of the mother’s gaze. Our bodily maps emerge from our primary caregivers and are not only organised by biology but by the idiosyncratic meanings held by parents, the wider family and the cultural system. As such, altering the body can be considered a sign of unconscious conflict, an attempt (a rather blatant one) to impose order, played out on the skin, the largest organ of the body. The tattooed person is exposing their inner turmoil and Lemma rejects the historic tendency to defend or over-idealise body-modification practices in the context of freedom or expression or the pursuit of spirituality, individuality and desire. At heart, she argues:

‘The more compulsive and extreme forms of body modification reflect a difficulty with integrating this most basic fact of life: we cannot give birth to ourselves.’

I wonder whether ‘extreme’ means the same thing in body art terms as it did when Lemma was writing or whether the goalposts have shifted. She seems to believe that more than one or two tattoos constitutes serial self-harm. What would she make of my designs growing into each other, intertwining and connecting, mimicking clematis?

Tattooing, according to Lemma, reflects different kinds of unconscious fantasy, all of which imply a disavowal of the body schema as something formed in collaboration. There is the ‘reclaiming’ fantasy, where the self is rescued from an alien presence felt to now reside in it, a process of banishing, casting out. There is the ‘perfect-match’ fantasy, where we strive to create an ‘ideal’ body which will guarantee the love and desire of the other. Then there is the more aggressive, ‘self-made’ fantasy in which we reject any notion of dependency and try to -literally - design ourselves. We seek the ‘monadic’ body, sealed from the perils of intimacy, a body-for-one. We are terrified of undifferentiation, obsessed with self-gratification rather than meaningful contact with others.

If the fantasy of being one’s own creator is enacted through rituals like tattooing, it is surely shown in less naked ways elsewhere. Like body modification, all gardening is inherently violent and all gardening involves grappling with control. In the end, it is all futile: the flesh disintegrates, the designs fade to blue, the garden is overtaken with weeds and then its finest blooms shrivel. We wear our hearts on our sleeves - I do so literally, a crimson talisman on my wrist. My mother’s heart is a clematis, a splayed, hopeful star. Her garden rests on soil which has been a political battleground. Her own body is ageing, troubled by illness, becoming Kristeva’s ‘abject’. The body, the earth - both have the last laugh.

My mother rejects tattoos in the disappointment I used to see across her face when she looked at mine, in refusing to admire her grandson’s transfer tattoos, proudly displayed on his lower arms. But perhaps I too have rejected her gardening - the hours I spent at allotments as a child, fettling soil with my hands, looking for worms, has not translated into an adult interest in cultivating plants and vegetables. I do not even try. I don’t think I could keep a garden alive. I remember my mother’s burden, the bags of compost too heavy to lift, the constant cycle of watering and planting. She was a martyr to the soil. Sometimes I’d watch her, stooping to dig, wearing her scruffiest clothes, hoping she might look up and notice me, remember how long we’d been there under the steely sky.

Why does psychoanalysis return so relentlessly to the impact of the mother and her searing gaze? In being there first with the child, she becomes a scapegoat for the world’s layered harms. This always seems to me to be an anticlimax, a disappointing failure of imagination. It distracts us from thinking about structure. If the gaze of the world is destabilising, it is not my mother’s fault. In tattooing my body, in wearing patterns I have chosen, I interrupt the gaze of the other in ways which cannot be predicted, are not predictable.

When I am tattooed, I am not thinking of my mother. If anything, I am perhaps thinking of the nonchalance with which others have tried to inscribe my body with an ideal of beauty which is not mine. I am rejecting their sense of flourishing femininity. I am thinking of Leonardo Da Vinci and his insistance that ‘human ingenuity…will never devise an invention more beautiful, more simple, more direct than does Nature’ and how countless male partners have invoked the idea of the ‘beautiful’ and the ‘natural’ to control my body in minor ways, from make-up to clothing to hairstyles to birth control to what and when and how much I ate. I am thinking of the potency and value of monadic rejection of intimacy and its ritual inscription on the skin in a culture where ‘no’ is seldom taken for an answer, where we can try to say no with our minds and our bodies and be forced anyway and then told we didn’t say it loudly enough. I am feeling sympathy with the damaged earth, with the open casting sites I grew up with, with all things touched and read and made useful without their permission.

Tattooing is metaphor. And it is a mistake to claim to have unravelled a metaphor, to fix a single meaning on it. The best images feel both exact and surprising, and this is because of the negative capability they induce in us, the Keatsian ideal of being able to live with a bit of mystery. I refuse to believe that we can generalise meaningfully about bodies which have already been inscribed by what they have been given or what they have overcome, by the ways others have looked at them, by pain or privilege.

If anything, I would like my mother to be indifferent to my tattoos. No, not indifferent: to be interested without judgement. If I invited her to, she could peer close and identify the different blooms, flowers that are only dying slowly. Peonies. Chrysanthemums. Perhaps one day a clematis. I’d like her to look at my altered state and find me as beautiful as I find her garden, no more, no less.