In his poem ‘Before You Cut Loose’, Simon Armitage evokes the nobility and devotion of dogs. Dogs belong on ‘the list / of difficult things to lose’. They have a unique homing instinct, a devotion to their Significant Humans:

…A dog might wander the width of the map

to bury its head in its owner’s lap,

crawl the last mile to dab a bleeding paw

against its own front door. To die at home,

a dog might walk its four legs to the bone….

I thought of that pathos on an overcast, mild early June day in Salford as my grey-and-fawn French Bulldog Denver sniffed at our esteemed Poet Laureate’s shoes, turned her back on the Manchester ship canal, circled three times and - with some ceremony - emptied her bowels. As first impressions go, it was quite notable. I’d joined Simon to record a radio piece about animals (more news about this in the autumn!) and two year old Denver was our accomplice for the day. Though, in true canine style, she was very much leading the way. We were duly taken for a walk.

Terrified of all dogs until my mid twenties, a devotee of whippets thereafter, author of a book about dogs in the mountains…..I never thought I’d be the proud owner of a flat-faced, bat-eared urban hound (and, for the record, I don’t condone the breeding practices that produce brachycephalic breeds). But when Denver came into my life last summer (rehomed, eager to jump on my lap and enjoy the adoration which all humans owe to her, sniffing my pockets for treats) it was impossible to resist her stubborn resolve, her unlikely athleticism, her pneumatic-drill snores. And as I researched the breed, I became fascinated by their history, an unlikely convergence of a-time-and-a-place.

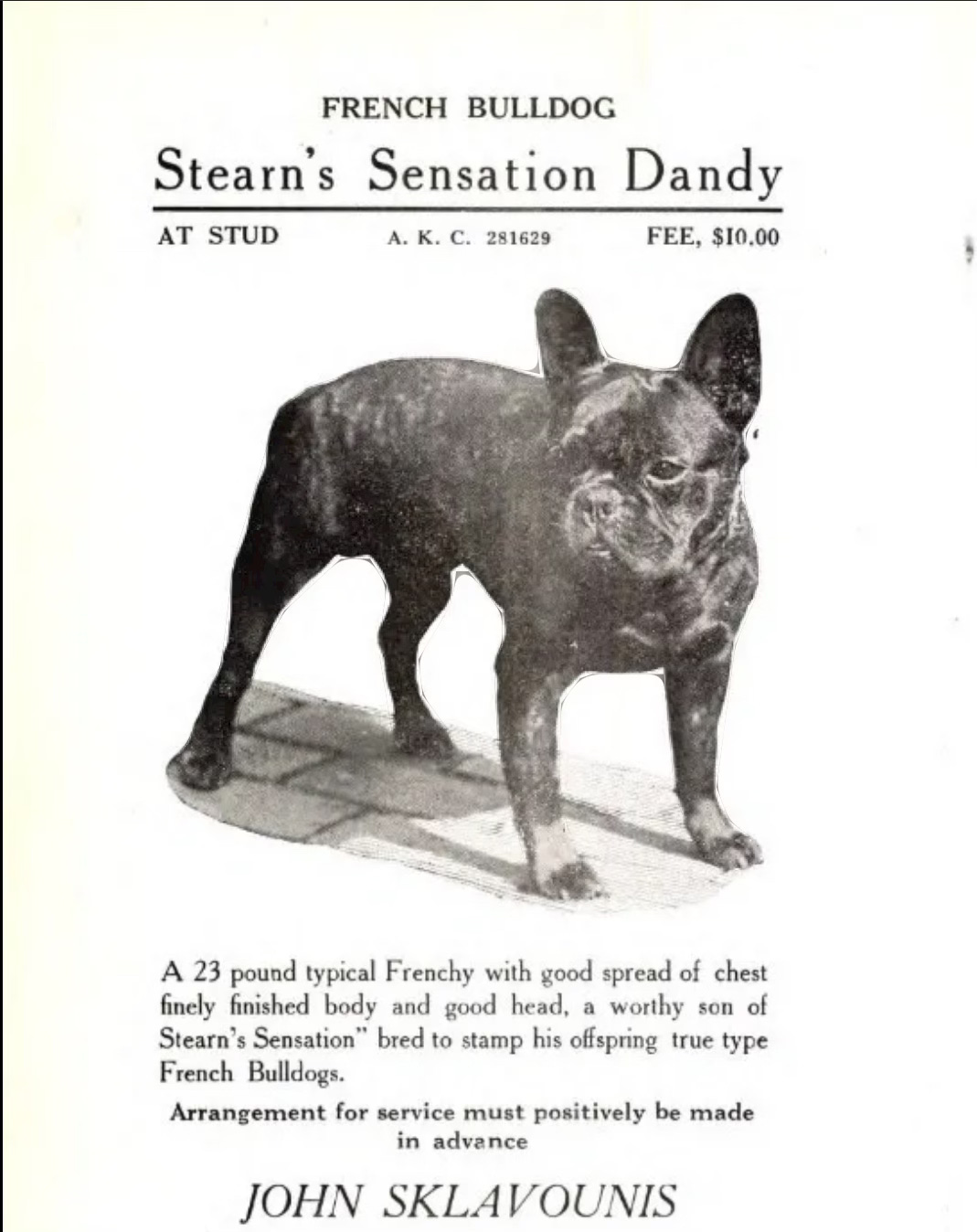

Confusingly, perhaps, the French Bulldog comes from England. In fact, for someone who grew up on the border between the East Midlands and South Yorkshire, they’re something of a pleasingly local phenomenon. Charmingly lazy, prone to occasional outbursts of energy, it’s difficult to imagine that Denver’s forebears had a relationship to industry. But Frenchies began as dogs for workers.

Lacemakers in Nottingham in the mid-1800s had smaller ‘toy’ Bulldogs who used to keep their laps warm as they worked (or so historians have guessed - the exact purpose is unknown). When the Industrial Revolution threatened the then cottage industry of lace making, many lacemakers relocated to France and took their canine companions with them. The lacemakers settled in the French countryside and over decades the ‘toy Bulldog’ is believed to have been bred with pugs and terriers to develop their distinct features including their instantly recognisable bat ears.

A trade in imported small Bulldogs was created, with breeders in England sending over dogs that they considered to be too tiny, or with ‘faults’ such as ears that stood up. By 1860, there were few Toy Bulldogs left in England, such was their popularity in France. Eventually, they found their way to Paris where they soon became synonymous with café life and Montmartre and received a breed name, the Bouledogue Francais (NB. a contraction of the words boule ('ball') and dogue ('mastiff')). Frenchies were a thing.

Artists such as Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec depict Frenchies in their paintings. The curious, loving creatures were highly sought after by society ladies and Parisian prostitutes alike and, in fact, they developed a close reputation as companion dogs for ‘ladies of the night’ (interestingly / bizarrely, my Frenchie will sometimes take a dislike to any man who she perceives to be a threat and I wonder if they were ever used to scare off difficult clients!). By the end of the 1800s their popularity begun spreading to Europe and America and today they’re an internet sensation, dressed up and cooed over all across the world. Post-lockdown, we’ve seen a surge in the numbers of Frenchies who end up in rescue shelters and some attribute this to the high vet bills that can be associated with the breed combined with a cost of living crisis.

French Bulldog by Toulouse-Lautrec

Perhaps the most intriguing French Bulldog lover in history is French author Colette, Nobel Prize winner, journalist and novelist. Known for her spirit of adventure (ahead of her time, maybe ahead of ours). Colette had many animals but she described her French Bulldog Toby-Chien as her ‘muse’. She was aware that the beauty of the Frenchie might not be immediately apparent to all observers. She said Toby was "an adorable creature whose face looked like a frog's that had been sat upon". He inspired much of her work (including a dialogue between cat and dog) and when Colette broke off her marriage with her husband, they tussled over the custody of Toby-Chien as if he was a child.

Image of Colette with Toby-Chien in the private gym in her apartment on Rue de Courcelles, 1910 (yes, she even had her own gym).

I commend the temperament of the Frenchie. If dogs are like their owners, I’ve come to see Denver as an unlikely-but-perfect fit for an author. They are sensitive but stubborn. They’re endlessly creative (how many ways can a Frenchie launch themselves onto a lap? Countless!). They demand 110% of your attention when they’re next to you, but they can be also be independent and aloof. They can sleep for hours but are prone to unpredictable, brief, near-violent outbursts of energy. If they don’t like the direction you’re taking them in, they sit down in protest. They’re needy, but endearingly so. And - despite appearances - they’re remarkably resilient. Expert performers, smart and agile, they succeed in keeping an audience. And, like poets, they delight in observation - just watch the radar dishes of their ears swivel as they watch!

Denver-Chien

Frenchies can be figures of fun. A friend described Denver as ‘so ugly she’s almost cute’. They’ve been heavily modified as a breed and I wouldn’t wish to make light of the health implications of that. But as I watch Denver scamper through the woods in front of me - charging at other dogs and spinning in giddy circles, pursuing a squirrel into undergrowth so dense I’m bound to have to lift her out - I prefer to think of them as ‘edited’ dogs. Imperfectly edited, captivating nonetheless. And who am I to argue with Colette?

My good friend the poet Alan Buckley sent me an umbrella this week. As a gift, that’s beautiful enough in itself: we should cherish friends who give us metaphors of shelter in tough times. But this was no ordinary umbrella either. For a start, it was lemon yellow. And it was adorned with Frenchies, tongues lolling, ears alert. Reader, these things of wonder do exist.

I leave you with a gorgeous poem by Jane Kenyon, ‘After An Illness,Walking The Dog’,