I have been thinking a lot this week about what it means to be wrong, or to be in the wrong, personally or politically (or indeed literally).

What would it mean to recognise wrong-ness in public? How often do we do that and – as a culture – how do we give people the opportunity to? How do we (should we?) make them feel it is safe to change their minds, to admit the possibility of wrong and the possibility of its transformation? Can ‘wrong’ be separated from shame?

*

I grew up in the house of a pedant. My dad often put grammar before all else. Even now with little independent mobility after a series of life-altering strokes, he’s been known to quibble over the precision of a certain instruction given to him: ‘you told me to move my left leg but not where to.’ Etc. My six year old son has inherited this pedantry and it delights me because it helps me see my father’s face in his.

*

‘Wrong ‘un’ was something they’d say about lads at school. I don’t know who ‘they’ were, but I presume they were elders and betters. ‘Stay away from him, he’s a bit of a wrong ‘un’. ‘Wrong’ created its own gravitational forcefield. Sexy. Banned.

*

One of my favourite poems of all time is Bill Matthews’ ‘Mingus at the Showplace’. The narrator is looking back on his late teenage years:

I was miserable, of course, for I was seventeen,

and so I swung into action and wrote a poem,and it was miserable, for that was how I thought

poetry worked: you digested experience and shatliterature…

On the night he’s recalling, the young poet ended up in a bar on West 4th Street, watching the acclaimed jazz musician Charles Mingus. We see him there, marooned on a high barstool. He makes the fatal mistake of asking the Great Man read his poem and is met with the response: ‘there’s a lot of that going around.’

But Mingus is not unkind. He laughs: ‘he didn’t look as if he thought / bad poems were dangerous, the way some poets do.’ Those are lines I try to cleave to in my own teaching, my attitude to work which comes from a different place to my own. I instinctively recoil at the idea that there is a ‘right’ or singular poetry, even though I’m sure I’m guilty of sweeping generalisations about what poetry ‘should’ be.

Later, Mingus fires one of his band members on stage, halfway through a number. The poem makes a deliberate show of hypocrisy. I like that. How people say things and do the opposite.

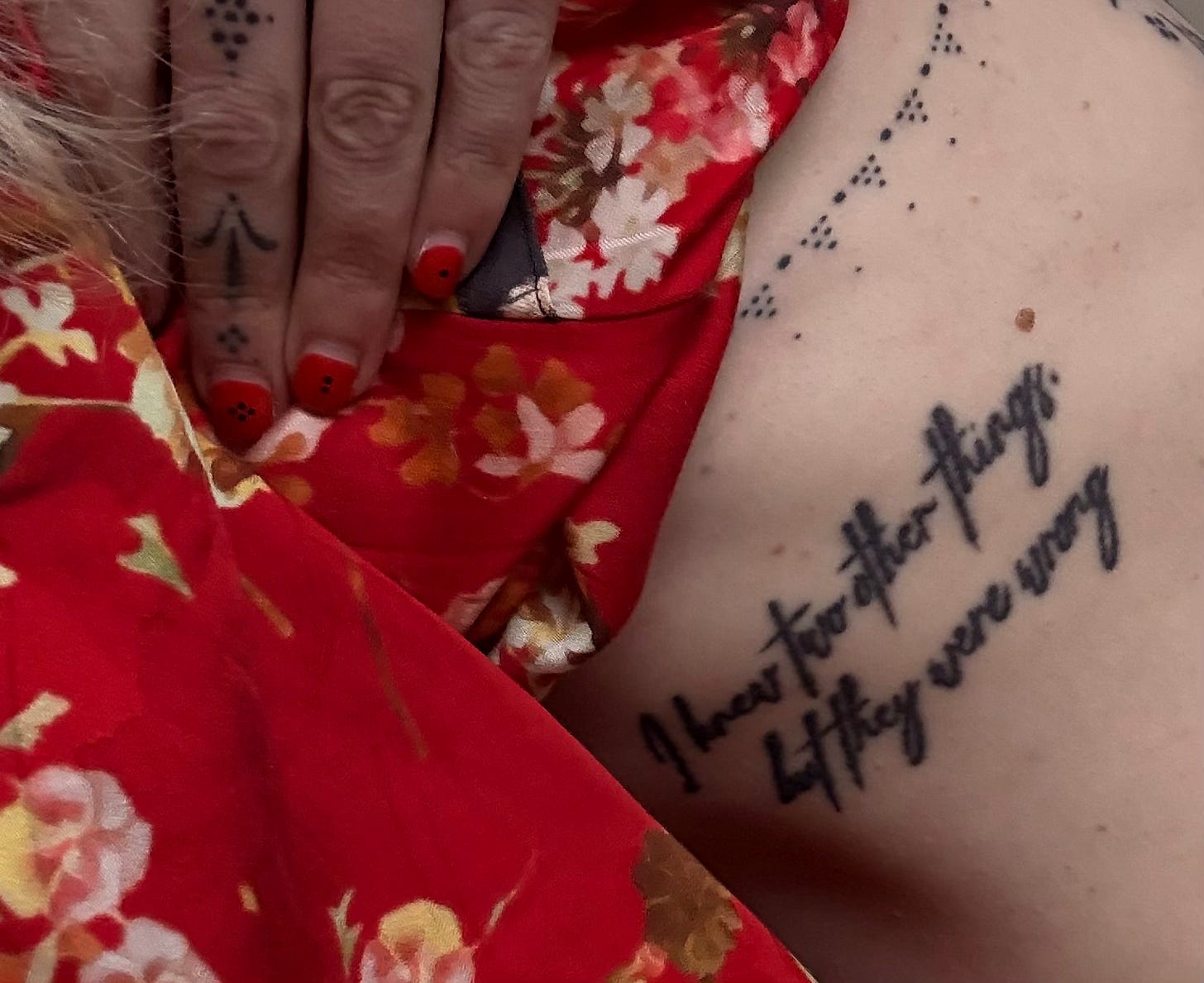

My favourite lines from ‘Mingus at the Showplace’ are these:

And I knew Mingus was a genius. I knew two

other things, but they were wrong, as it happened.

I like that stanza so much I have words from it tattooed on my ribcage. If you don’t believe me, I’ll show you.

*

Imposter syndrome: I’m doing it all wrong.

People in therapy for their imposter syndrome: I’m doing therapy wrong.

*

My father always did a lot of crosswords. When we used to attempt them together, when I was a child, I’d often rush to pencil in a word before we were sure of it and he’d chastise me. In the crossword grid, there is a right answer and there are answers that will always be wrong. It is that simple. Black and white.

*

‘In the wrong’: it sounds like a place. I was in Scunthorpe last week. I was in the wrong last week. I woke up and found myself in Plymouth / the dog house / the wrong. Etc. If wrong is a location, how do we sell our houses there and move when nobody will want to buy them?

*

I went on University Challenge once. I got almost everything wrong, even the things I knew.

*

When it comes to issues we care deeply about, a discourse of wrong / right and moral absolutism will inevitably develop. Perhaps there are good reasons why it should, the pressure of generating moral imperative, enacting change. We see it overwhelmingly on social media. Articulating subjects which feel life-and-death because they ARE, we may end up attacking others for not being ‘right’ soon enough as well as for being wrong.

If there is a right side of history to be on, how might someone cross over to it? Do we actually want them to? And if we do accept that they can cross, what do we have to sacrifice to let them in? Should it be a condition of passage that they admit their wrong-ness, in public or in private? I am asking these questions because I don’t know. To not know instantly may in itself be a kind of wrong.

*

The politician usually admits (s)he was wrong only while pointing out of the window. We look, we see a fire started by someone else.

*

At the other end of the spectrum, we find the low-stakes pub argument, usually over a point of memory, of recalled or mis-recalled fact. Pub quizzes draw it out of us. Now that we have smartphones, the ‘right’ answer always seems tantalisingly close. What happens if we don’t Google it?

Pub quiz rounds I have enjoyed: ‘cheese or service station?’. A series of names read out. Which was which?

*

Alva de Campos in “No, you’re right, I’m wrong”:

No, you’re right, I’m wrong ...

Allow me to drift off from this pointless argument,

I’m wrong in my opinion, that’s fine, I’m not deeply attached to that opinion anyway ...I’m not even listening, you say? I don’t know.

I think I am. But repeat what you just said.

Love should be constant?

Yes, it should be constant.

But only in love, of course.

Say it again, will you? ...

*

What happens if you feel you are wronging someone else to do right by yourself?

*

Right place, wrong time. Wrong place, right time. Wrong person, wrong time. Right person –

*

My son and his friend have been having an argument about infinity. Is it a number or a concept? Alfie says number. His friend disagrees. I tell him they are both sort-of right, that some things can be both. He is displeased with this answer. He stomps off to play on his Nintendo Switch.

*

Poetry isn’t helping matters, is it? Sometimes I say that I like poems because they are capable of embodying a paradox: two simultaneous truths. Negative capability. But quite often, the voice of the poem is very certain indeed. Some poems – however deliberately surreal or ludicrous – succeed because they create the illusion of certainty. As a reader, this can make us feel safe rather than deceived.

Take another of my favourite poems, ‘Country Fair’ by Charles Simic. It starts like this:

If you didn't see the six-legged dog,

It doesn't matter.

We did, and he mostly lay in the corner.

As for the extra legsOne got used to them quickly

And thought of other things

like, what a cold, dark night

To be out at the fair…

This opening works because I trust the authority of the narrator. No, I am beguiled by it. I believe that there is a six-legged dog and that, once I have imagined it, I have to pretend it is incidental. This is only half the story, of course.

I have a confidence of tone in my writing that I often lack in the rest of life. I can assert the bizarre, the fleeting, the improbable. We know that the rhetoric of poetry is not like the rhetoric of political speech, but how are we to feel about the shared persuasive territory they occupy?

*

The words ‘territory’ and ‘occupy’ close together cannot be separated from fundamental wrong. There are so many phrases I use which I later find problematic. Don’t worry, I’ll be up all night, turning it over.

*

Can I be wronged by you if you did not mean to wrong me? Is wrongness ever in the eye of the beholder?

*

Sometimes I also say that the poem is a ‘collaboration between author and reader’. In this sense, there are no ‘wrong’ readings, only subjective interpretations. But most of the time, this is a platitude. If you tell me my poem about my dead grandmother is really about my love of frogs, I might get angry with you. All readings are equal but some readings are more equal than others.

*

On the second day of a mountain marathon in North West Scotland, in blistering summer heat, I decided to help my running partner Andrew with the navigation, feeling I hadn’t pulled my weight with the orienetering aspect of the challenge. I squinted at the map. I mis-read it. I sent us to the wrong lochan. A wasted hour, slogging uphill through bracken through a point we weren’t supposed to reach, then another hour sliding back down on shifting scree. I waited for him to be angry with me. He said:

“I treat navigation like a pub quiz. You’re a team. If you let someone else puts down the wrong answer and you don’t correct them or offer anything better, it’s as much your fault as theirs.”

I loved him for saying that. Still do.

*

‘NO REGERTS’ is a popular joke tattoo. The joyful display of a wrongness.

My tattooist friend says ‘guilt is a pointless emotion.’

*

Are we saying there are different qualities of wrong? Can you enter a sliding scale, wrong and then wronger and then wrongest of all?

*

Wrong as in ‘off’. Wrong as in feeling skewed, unbalanced, not yourself. ‘It looks a bit wrong somehow.’ ‘I don’t feel quite right today’ – the wrongness there in absentia, still making itself known. The important silence of an important person, or a person you have made important, giving them the power to wrong you.

*

Bill Matthews in ‘Poems from WRONG’:

What’s wrong is to live by corrections, to be good

For a living – proofreader, inspector of public works –To go into the tunnels of error like a rat tarrier

And come out and know you will be fed for it.

*

Sometimes, I find it easier to say I was wrong only after a suitable interval has passed. A wrongness lag.

*

I knew two things.

I knew two other things.

I knew two other things and they -