I recently returned from a short trip to Port Renfrew, British Columbia and what A Time and a Place it was. The rainiest part of Canada, the great Pacific North West coast where trees feel like slumbering giants and otters and eagles and Great Blue herons visit. At Botanical Beach, even the mussel shells are large, shot through with porcelain blues and iridescent silver. Held aloft, they look like hunched wings. There are birds I’d never encountered. I even saw my first Banana Slug (yes, they are real!)

A banana slug!

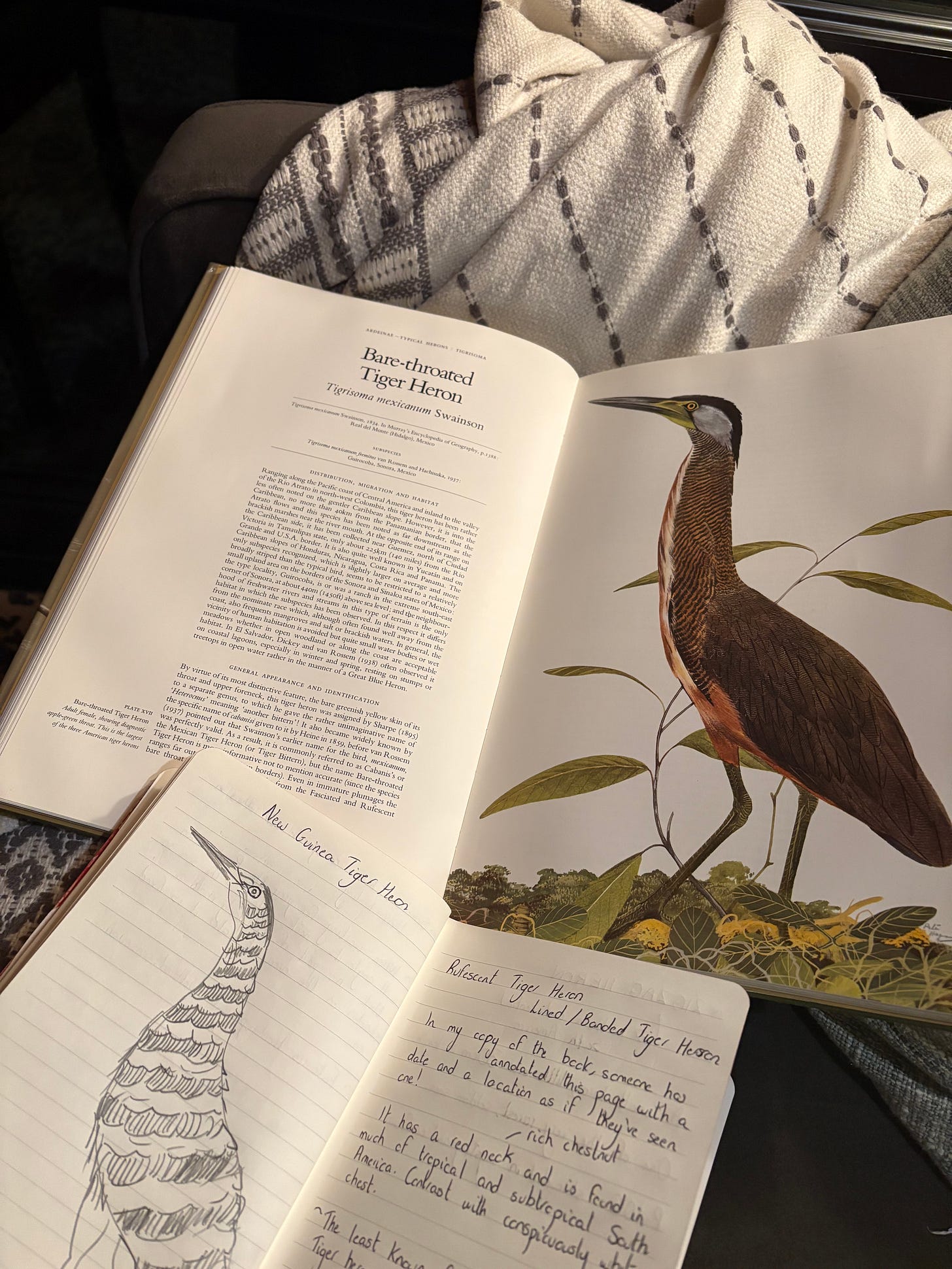

Port Renfrew is a tiny town on the land of the Pacheedaht First Nations people. I was visiting to write about herons, these everyday-remarkable birds that stand fencepost-still in shallow waters then open the huge umbrellas of their wings when you least expect it. I found them in abundance, on the shores of Harris Cove and in the literature I was reading, a giant bird encyclopaedia with detailed drawings of each variety of bittern, heron, egret. I sketched the herons by night, trying to memorise their names. Japanese Night Heron. Tiger Heron. Slaty Egret. But Port Renfrew also yielded some surprising stories, Time-and-Place inflected.

Being on the edge of Vancouver Island is a good cure for any sense of your own self-importance. The Red Cedars are so vast that it is humbling just to look at them. There are Sitka Spruce with dark, feathered trunks and twisting Douglas Fir trees. 10 kilometres from Port Renfrew in the Gordon River Valley stands Big Lonely Doug, some 70 metres tall, a great sentinel of a Douglas Fir Tree, islanded and alone.

Big Lonely Doug from below

In 2011, logger Dennis Cronin discovered the enormous tree while surveying a patch of forest that was to be logged, known as cutblock 7190. The trunk was wider than a car and it was almost as tall as a twenty storey building. Cronin knew it was one of the biggest trees he had ever seen. He wrapped green ribbon around it with the words "Leave Tree" repeated along the ribbon, saving it from being felled for timber. Within a year, the rest of cutblock 7190 – the copious cedars, hemlocks and firs - would be gone. Three years later, a photographer and activist called T.J. Watt happened upon the tree and named it "Big Lonely Doug", a play on the species name and its relative isolation amid the clearcut. Doug stands as patiently as a heron in water. It makes everything around it seem insignificant.

Today, it is one of the last of a threatened species in coastal BC, where 99 percent of the old-growth Douglas firs have been logged. If you want to understand the old-growth forest of British Columbia and the complex emblem of environmental activism Doug has become, you need to read the book ‘Big Lonely Doug’ by Harley Rustad. Or you could start with the shorter article he wrote for The Walrus. In it, Rustad gives context to Canada’s old-growth Pacific temperate rainforest and its value. The patches of old-growth ‘were once part of a thick band that fringed the continent from Alaska to northern California.’ There is tremendous variety to be found there:

‘Under the dark-green foliage, thick salal bushes make one section impenetrable to pedestrians; another opens into a clearing. Some trees appear painted in lime-green moss, while others drip with grey lichen. The larger trees pierce the canopy, allowing long beams of light to penetrate. ….On the ground, a blown-down cedar can lie nearly intact for a century, slowly decomposing and becoming a “nurse log” in which opportunistic seedlings can take root. Any tree that falls, anything that dies, remains. Every hectare contains more biomass—the total volume of live and decaying flora and fauna—than any other ecosystem on the planet, greater even than the tropics, where the heat breaks down dead matter more quickly. Life teems in every square metre: insects, fungi, birds. One researcher has shown that 18,000 invertebrates can be found under a single pair of boot prints. Not only are these forests more efficient at absorbing carbon from the atmosphere than smaller second-growth trees, they also present one of the few environments in the world where large carnivores (wolves, mountain lions, and bears) and ungulates (deer and elk) exist alongside some of the biggest trees. The Douglas firs in particular play a key role, transferring nutrients from their great heights to smaller saplings below through mycorrhizal fungi that link together the roots of various species in an underground network.’

I saw a nurse log in Eden Grove near where Doug stands, new growth emerging from it. It was remarkable - the new and the old not just co-existing but intertwined. The quality of silence seemed different in the grove. It was lush and spooky. In the 1990s, these forests became contested as anti-logging protestors began to fight back against the industry, the startling fact that ‘while it could take 500 years for a fir to reach fifty metres tall and two metres wide, it can take a skilled faller with a chainsaw five minutes to bring it down.’

In the early ‘90s, the ‘War in the Woods’ took place in nearby Tofino, a stand off between timber workers and environmentalists. For the Ancient Forest Alliance (AFA), Doug was just the emblem they needed to help advance their argument that – though logging is lucrative – cutting down Vancouver Island’s great trees is damaging and counterproductive. As Rustad notes, it is a complex issue and while Big Lonely Doug is ‘safe’, a tourist attraction even, around it:

‘…the battle continues. The provincial government still approves logging leases on patches of old growth in unprotected areas. And timber is still big business in BC, where one in sixteen jobs is related to the forest industry, which annually contributes $12 billion to the provincial GDP.’

He continues:

‘But while cutting down old-growth forest may be profitable in the short term, there also is an economic argument to be made for keeping these trees standing. Only 10 percent of the original forests that hold the giants remain on Vancouver Island. Given the value of old-growth as a draw for eco-tourists, long-term economic output might well be maximized if the logging industry were to focus on second-growth forest, which covers much of the island….Cutting old growth, in other words, represents a complete lack of foresight. We are on the cusp of losing the last remaining giant trees of Vancouver Island, and it won’t take a few years or a decade but many centuries to get this resource back.’

Standing under Big Lonely Doug and looking up, you become acutely aware of how limited our human imagination is. I thought of the ‘living forms’ in the boat-stealing episode in Wordsworth’s Prelude, how he feels pursued by the landscape and can’t shake the image of a ‘huge peak, black and huge’ for days. Awe. You can try to picture Doug’s vast root network, but it’s almost impossible to comprehend. Harder still to truly engage with the age of it, the idea of it standing for a thousand years. It is an emblem of contested beauty, of struggle and loss.

Perhaps Cronin summarised some of the strange contradictions and complexities that surround Doug when he said simply: “I’m glad it grabbed everybody’s attention. Nobody would have ever seen it if we hadn’t logged that piece.”

Buy Harley’s book on Big Lonely Doug here.